UUCP and Usenet

In 1979, two students at Duke University, Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis, originated the idea of using Bourne shell scripts to transfer news and messages on a serial line UUCP connection with nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Following public release of the software in 1980, the mesh of UUCP hosts forwarding on the Usenet news rapidly expanded. UUCPnet, as it would later be named, also created gateways and links between FidoNet and dial-up BBS hosts. UUCP networks spread quickly due to the lower costs involved, ability to use existing leased lines, X.25 links or even ARPANET connections, and the lack of strict use policies compared to later networks like CSNET and Bitnet. All connects were local. By 1981 the number of UUCP hosts had grown to 550, nearly doubling to 940 in 1984. – Sublink Network, operating since 1987 and officially founded in Italy in 1989, based its interconnectivity upon UUCP to redistribute mail and news groups messages throughout its Italian nodes (about 100 at the time) owned both by private individuals and small companies. Sublink Network represented possibly one of the first examples of the Internet technology becoming progress through popular diffusion.[59]

Merging the networks and creating the Internet (1973–95)

TCP/IP

With so many different network methods, something was needed to unify them. Robert E. Kahn of DARPA and ARPANET recruited Vinton Cerf of Stanford University to work with him on the problem. By 1973, they had worked out a fundamental reformulation, where the differences between network protocols were hidden by using a common internetwork protocol, and instead of the network being responsible for reliability, as in the ARPANET, the hosts became responsible. Cerf credits Hubert Zimmermann, Gerard LeLann, Louis Pouzin (designer of the CYCLADES network),[60] and his graduate students Judy Estrin, Richard Karp, Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine with important work on this design.[61] This Stanford research team became known as the International Network Working Group, formed in 1973 and led by Cerf.[62]

The specification of the resulting protocol, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), was published as RFC 675 by the Network Working Group in December 1974.[63] It contains the first attested use of the term internet, as a shorthand for internetworking.

Between 1976 and 1977, Yogen Dalal proposed separating TCP's routing and transmission control functions into two discrete layers,[64][65] which led to the splitting of TCP into the TCP and IP protocols, and the development of TCP/IP.[65]

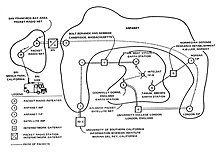

With the role of the network reduced to a core of functionality, it became possible to exchange traffic with other network independently from their detailed characteristics, thereby solving Kahn's initial problem. DARPA agreed to fund development of prototype software, and after several years of work, the first demonstration of a gateway between the Packet Radio network in the SF Bay area and the ARPANET was conducted by the Stanford Research Institute. On November 22, 1977 a three network demonstration was conducted including the ARPANET, the SRI's Packet Radio Van on the Packet Radio Network and the Atlantic Packet Satellite network.[66][67]

Stemming from the first specifications of TCP in 1974, TCP/IP emerged in 1978 in nearly its final form, as used for the first decades of the Internet.[68] which is described in IETF publication RFC 791 (September 1981).

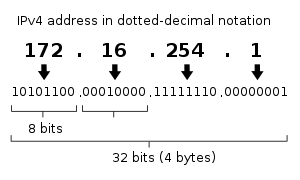

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses which limits the address space to 232 addresses, i.e. 4294967296 addresses.[68] The last available IPv4 address was assigned in January 2011.[69] IPv4 is being replaced by its successor, called "IPv6", which uses 128 bit addresses, providing 2128 addresses, i.e. 340282366920938463463374607431768211456.[70] This is a vastly increased address space. The shift to IPv6 is expected to take many years, decades, or perhaps longer, to complete, since there were four billion machines with IPv4 when the shift began.[69]

The associated standards for IPv4 were published by 1981 as RFCs 791, 792 and 793, and adopted for use. DARPA sponsored or encouraged the development of TCP/IP implementations for many operating systems and then scheduled a migration of all hosts on all of its packet networks to TCP/IP. On January 1, 1983, known as flag day, TCP/IP protocols became the standard for the ARPANET, replacing the earlier NCP protocol.[71]

From ARPANET to NSFNET

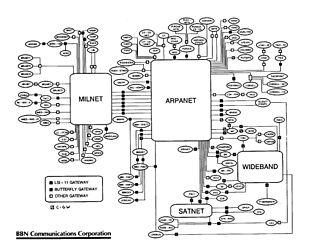

After the ARPANET had been up and running for several years, ARPA looked for another agency to hand off the network to; ARPA's primary mission was funding cutting edge research and development, not running a communications utility. Eventually, in July 1975, the network had been turned over to the Defense Communications Agency, also part of the Department of Defense. In 1983, the U.S. military portion of the ARPANET was broken off as a separate network, the MILNET. MILNET subsequently became the unclassified but military-only NIPRNET, in parallel with the SECRET-level SIPRNET and JWICS for TOP SECRET and above. NIPRNET does have controlled security gateways to the public Internet.

The networks based on the ARPANET were government funded and therefore restricted to noncommercial uses such as research; unrelated commercial use was strictly forbidden. This initially restricted connections to military sites and universities. During the 1980s, the connections expanded to more educational institutions, and even to a growing number of companies such as Digital Equipment Corporation and Hewlett-Packard, which were participating in research projects or providing services to those who were.

Several other branches of the U.S. government, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Department of Energy (DOE) became heavily involved in Internet research and started development of a successor to ARPANET. In the mid-1980s, all three of these branches developed the first Wide Area Networks based on TCP/IP. NASA developed the NASA Science Network, NSF developed CSNET and DOE evolved the Energy Sciences Network or ESNet.

NASA developed the TCP/IP based NASA Science Network (NSN) in the mid-1980s, connecting space scientists to data and information stored anywhere in the world. In 1989, the DECnet-based Space Physics Analysis Network (SPAN) and the TCP/IP-based NASA Science Network (NSN) were brought together at NASA Ames Research Center creating the first multiprotocol wide area network called the NASA Science Internet, or NSI. NSI was established to provide a totally integrated communications infrastructure to the NASA scientific community for the advancement of earth, space and life sciences. As a high-speed, multiprotocol, international network, NSI provided connectivity to over 20,000 scientists across all seven continents.

In 1981 NSF supported the development of the Computer Science Network (CSNET). CSNET connected with ARPANET using TCP/IP, and ran TCP/IP over X.25, but it also supported departments without sophisticated network connections, using automated dial-up mail exchange.

In 1986, the NSF created NSFNET, a 56 kbit/s backbone to support the NSF-sponsored supercomputing centers. The NSFNET also provided support for the creation of regional research and education networks in the United States, and for the connection of university and college campus networks to the regional networks.[72] The use of NSFNET and the regional networks was not limited to supercomputer users and the 56 kbit/s network quickly became overloaded. NSFNET was upgraded to 1.5 Mbit/s in 1988 under a cooperative agreement with the Merit Network in partnership with IBM, MCI, and the State of Michigan. The existence of NSFNET and the creation of Federal Internet Exchanges (FIXes) allowed the ARPANET to be decommissioned in 1990. NSFNET was expanded and upgraded to 45 Mbit/s in 1991, and was decommissioned in 1995 when it was replaced by backbones operated by several commercial Internet service providers.

Transition towards the Internet

The term "internet" was reflected in the first RFC published on the TCP protocol (RFC 675:[73] Internet Transmission Control Program, December 1974) as a short form of internetworking, when the two terms were used interchangeably. In general, an internet was a collection of networks linked by a common protocol. In the time period when the ARPANET was connected to the newly formed NSFNET project in the late 1980s, the term was used as the name of the network, Internet, being the large and global TCP/IP network.[74]

As interest in networking grew by needs of collaboration, exchange of data, and access of remote computing resources, the TCP/IP technologies spread throughout the rest of the world. The hardware-agnostic approach in TCP/IP supported the use of existing network infrastructure, such as the IPSS X.25 network, to carry Internet traffic. In 1982, one year earlier than the ARPANET, University College London replaced its transatlantic satellite links with TCP/IP over IPSS.[75][76]

Many sites unable to link directly to the Internet created simple gateways for the transfer of electronic mail, the most important application of the time. Sites with only intermittent connections used UUCP or FidoNet and relied on the gateways between these networks and the Internet. Some gateway services went beyond simple mail peering, such as allowing access to File Transfer Protocol (FTP) sites via UUCP or mail.[77]

Finally, routing technologies were developed for the Internet to remove the remaining centralized routing aspects. The Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) was replaced by a new protocol, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). This provided a meshed topology for the Internet and reduced the centric architecture which ARPANET had emphasized. In 1994, Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) was introduced to support better conservation of address space which allowed use of route aggregation to decrease the size of routing tables.[78]

TCP/IP goes global (1980s)

CERN, the European Internet, the link to the Pacific and beyond

Between 1984 and 1988 CERN began installation and operation of TCP/IP to interconnect its major internal computer systems, workstations, PCs and an accelerator control system. CERN continued to operate a limited self-developed system (CERNET) internally and several incompatible (typically proprietary) network protocols externally. There was considerable resistance in Europe towards more widespread use of TCP/IP, and the CERN TCP/IP intranets remained isolated from the Internet until 1989.

In 1988, Daniel Karrenberg, from Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI) in Amsterdam, visited Ben Segal, CERN's TCP/IP Coordinator, looking for advice about the transition of the European side of the UUCP Usenet network (much of which ran over X.25 links) over to TCP/IP. In 1987, Ben Segal had met with Len Bosack from the then still small company Cisco about purchasing some TCP/IP routers for CERN, and was able to give Karrenberg advice and forward him on to Cisco for the appropriate hardware. This expanded the European portion of the Internet across the existing UUCP networks, and in 1989 CERN opened its first external TCP/IP connections.[79] This coincided with the creation of Réseaux IP Européens (RIPE), initially a group of IP network administrators who met regularly to carry out coordination work together. Later, in 1992, RIPE was formally registered as a cooperative in Amsterdam.

At the same time as the rise of internetworking in Europe, ad hoc networking to ARPA and in-between Australian universities formed, based on various technologies such as X.25 and UUCPNet. These were limited in their connection to the global networks, due to the cost of making individual international UUCP dial-up or X.25 connections. In 1989, Australian universities joined the push towards using IP protocols to unify their networking infrastructures. AARNet was formed in 1989 by the Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee and provided a dedicated IP based network for Australia.

The Internet began to penetrate Asia in the 1980s. In May 1982 South Korea became the second country to successfully set up TCP/IP IPv4 network.[80][81] Japan, which had built the UUCP-based network JUNET in 1984, connected to NSFNET in 1989. It hosted the annual meeting of the Internet Society, INET'92, in Kobe. Singapore developed TECHNET in 1990, and Thailand gained a global Internet connection between Chulalongkorn University and UUNET in 1992.[82]

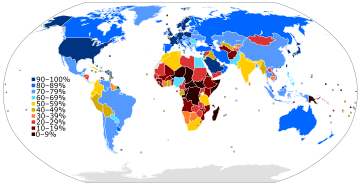

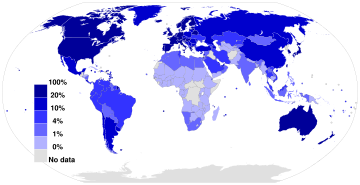

The early global "digital divide" emerges

While developed countries with technological infrastructures were joining the Internet, developing countries began to experience a digital divide separating them from the Internet. On an essentially continental basis, they are building organizations for Internet resource administration and sharing operational experience, as more and more transmission facilities go into place.

Africa

At the beginning of the 1990s, African countries relied upon X.25 IPSS and 2400 baud modem UUCP links for international and internetwork computer communications.

In August 1995, InfoMail Uganda, Ltd., a privately held firm in Kampala now known as InfoCom, and NSN Network Services of Avon, Colorado, sold in 1997 and now known as Clear Channel Satellite, established Africa's first native TCP/IP high-speed satellite Internet services. The data connection was originally carried by a C-Band RSCC Russian satellite which connected InfoMail's Kampala offices directly to NSN's MAE-West point of presence using a private network from NSN's leased ground station in New Jersey. InfoCom's first satellite connection was just 64 kbit/s, serving a Sun host computer and twelve US Robotics dial-up modems.

In 1996, a USAID funded project, the Leland Initiative, started work on developing full Internet connectivity for the continent. Guinea, Mozambique, Madagascar and Rwanda gained satellite earth stations in 1997, followed by Ivory Coast and Benin in 1998.

Africa is building an Internet infrastructure. AFRINIC, headquartered in Mauritius, manages IP address allocation for the continent. As do the other Internet regions, there is an operational forum, the Internet Community of Operational Networking Specialists.[86]

There are many programs to provide high-performance transmission plant, and the western and southern coasts have undersea optical cable. High-speed cables join North Africa and the Horn of Africa to intercontinental cable systems. Undersea cable development is slower for East Africa; the original joint effort between New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) and the East Africa Submarine System (Eassy) has broken off and may become two efforts.[87]

Asia and Oceania

The Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), headquartered in Australia, manages IP address allocation for the continent. APNIC sponsors an operational forum, the Asia-Pacific Regional Internet Conference on Operational Technologies (APRICOT).[88]

South Korea's first Internet system, the System Development Network (SDN) began operation on 15 May 1982. SDN was connected to the rest of the world in August 1983 using UUCP (Unixto-Unix-Copy); connected to CSNET in December 1984; and formally connected to the U.S. Internet in 1990.[89]

In 1991, the People's Republic of China saw its first TCP/IP college network, Tsinghua University's TUNET. The PRC went on to make its first global Internet connection in 1994, between the Beijing Electro-Spectrometer Collaboration and Stanford University's Linear Accelerator Center. However, China went on to implement its own digital divide by implementing a country-wide content filter.[90]

Latin America

As with the other regions, the Latin American and Caribbean Internet Addresses Registry (LACNIC) manages the IP address space and other resources for its area. LACNIC, headquartered in Uruguay, operates DNS root, reverse DNS, and other key services.

Rise of the global Internet (late 1980s/early 1990s onward)

Initially, as with its predecessor networks, the system that would evolve into the Internet was primarily for government and government body use.

However, interest in commercial use of the Internet quickly became a commonly debated topic. Although commercial use was forbidden, the exact definition of commercial use was unclear and subjective. UUCPNet and the X.25 IPSS had no such restrictions, which would eventually see the official barring of UUCPNet use of ARPANET and NSFNET connections. (Some UUCP links still remained connecting to these networks however, as administrators cast a blind eye to their operation.)[citation needed]

As a result, during the late 1980s, the first Internet service provider (ISP) companies were formed. Companies like PSINet, UUNET, Netcom, and Portal Software were formed to provide service to the regional research networks and provide alternate network access, UUCP-based email and Usenet News to the public. The first commercial dialup ISP in the United States was The World, which opened in 1989.[92]

In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed the Scientific and Advanced-Technology Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1862(g), which allowed NSF to support access by the research and education communities to computer networks which were not used exclusively for research and education purposes, thus permitting NSFNET to interconnect with commercial networks.[93][94] This caused controversy within the research and education community, who were concerned commercial use of the network might lead to an Internet that was less responsive to their needs, and within the community of commercial network providers, who felt that government subsidies were giving an unfair advantage to some organizations.[95]

By 1990, ARPANET's goals had been fulfilled and new networking technologies exceeded the original scope and the project came to a close. New network service providers including PSINet, Alternet, CERFNet, ANS CO+RE, and many others were offering network access to commercial customers. NSFNET was no longer the de facto backbone and exchange point of the Internet. The Commercial Internet eXchange (CIX), Metropolitan Area Exchanges (MAEs), and later Network Access Points (NAPs) were becoming the primary interconnections between many networks. The final restrictions on carrying commercial traffic ended on April 30, 1995 when the National Science Foundation ended its sponsorship of the NSFNET Backbone Service and the service ended.[96][97] NSF provided initial support for the NAPs and interim support to help the regional research and education networks transition to commercial ISPs. NSF also sponsored the very high speed Backbone Network Service (vBNS) which continued to provide support for the supercomputing centers and research and education in the United States.[98]

World Wide Web and introduction of browsers

The World Wide Web (sometimes abbreviated "www" or "W3") is an information space where documents and other web resources are identified by URIs, interlinked by hypertext links, and can be accessed via the Internet using a web browser and (more recently) web-based applications.[99] It has become known simply as "the Web". As of the 2010s, the World Wide Web is the primary tool billions use to interact on the Internet, and it has changed people's lives immeasurably.[100][101][102]

Precursors to the web browser emerged in the form of hyperlinked applications during the mid and late 1980s (the bare concept of hyperlinking had by then existed for some decades). Following these, Tim Berners-Lee is credited with inventing the World Wide Web in 1989 and developing in 1990 both the first web server, and the first web browser, called WorldWideWeb (no spaces) and later renamed Nexus.[103] Many others were soon developed, with Marc Andreessen's 1993 Mosaic (later Netscape),[104] being particularly easy to use and install, and often credited with sparking the Internet boom of the 1990s.[105] Other major web browsers have been Internet Explorer, Firefox, Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Opera and Safari.[106]

NCSA Mosaic was a graphical browser which ran on several popular office and home computers.[107] It is credited with first bringing multimedia content to non-technical users by including images and text on the same page, unlike previous browser designs;[108] Marc Andreessen, its creator, also established the company that in 1994, released Netscape Navigator, which resulted in one of the early browser wars, when it ended up in a competition for dominance (which it lost) with Microsoft Windows' Internet Explorer. Commercial use restrictions were lifted in 1995. The online service America Online (AOL) offered their users a connection to the Internet via their own internal browser.

Use in wider society 1990s to early 2000s (Web 1.0)

During the first decade or so of the public Internet, the immense changes it would eventually enable in the 2000s were still nascent. In terms of providing context for this period, mobile cellular devices ("smartphones" and other cellular devices) which today provide near-universal access, were used for business and not a routine household item owned by parents and children worldwide. Social media in the modern sense had yet to come into existence, laptops were bulky and most households did not have computers. Data rates were slow and most people lacked means to video or digitize video; media storage was transitioning slowly from analog tape to digital optical discs (DVD and to an extent still, floppy disc to CD). Enabling technologies used from the early 2000s such as PHP, modern JavaScript and Java, technologies such as AJAX, HTML 4 (and its emphasis on CSS), and various software frameworks, which enabled and simplified speed of web development, largely awaited invention and their eventual widespread adoption.

The Internet was widely used for mailing lists, emails, e-commerce and early popular online shopping (Amazon and eBay for example), online forums and bulletin boards, and personal websites and blogs, and use was growing rapidly, but by more modern standards the systems used were static and lacked widespread social engagement. It awaited a number of events in the early 2000s to change from a communications technology to gradually develop into a key part of global society's infrastructure.

Typical design elements of these "Web 1.0" era websites included:[109] Static pages instead of dynamic HTML;[110] content served from filesystems instead of relational databases; pages built using Server Side Includes or CGI instead of a web application written in a dynamic programming language; HTML 3.2-era structures such as frames and tables to create page layouts; online guestbooks; overuse of GIF buttons and similar small graphics promoting particular items;[111] and HTML forms sent via email. (Support for server side scripting was rare on shared servers so the usual feedback mechanism was via email, using mailto forms and their email program.[112]

During the period 1997 to 2001, the first speculative investment bubble related to the Internet took place, in which "dot-com" companies (referring to the ".com" top level domain used by businesses) were propelled to exceedingly high valuations as investors rapidly stoked stock values, followed by a market crash; the first dot-com bubble. However this only temporarily slowed enthusiasm and growth, which quickly recovered and continued to grow.

The changes that would propel the Internet into its place as a social system took place during a relatively short period of no more than five years, starting from around 2004. They included:

- The call to "Web 2.0" in 2004 (first suggested in 1999),

- Accelerating adoption and commoditization among households of, and familiarity with, the necessary hardware (such as computers).

- Accelerating storage technology and data access speeds – hard drives emerged, took over from far smaller, slower floppy discs, and grew from megabytes to gigabytes (and by around 2010, terabytes), RAM from hundreds of kilobytes to gigabytes as typical amounts on a system, and Ethernet, the enabling technology for TCP/IP, moved from common speeds of kilobits to tens of megabits per second, to gigabits per second.

- High speed Internet and wider coverage of data connections, at lower prices, allowing larger traffic rates, more reliable simpler traffic, and traffic from more locations,

- The gradually accelerating perception of the ability of computers to create new means and approaches to communication, the emergence of social media and websites such as Twitter and Facebook to their later prominence, and global collaborations such as Wikipedia (which existed before but gained prominence as a result),

and shortly after (approximately 2007–2008 onward):

- The mobile revolution, which provided access to the Internet to much of human society of all ages, in their daily lives, and allowed them to share, discuss, and continually update, inquire, and respond.

- Non-volatile RAM rapidly grew in size and reliability, and decreased in price, becoming a commodity capable of enabling high levels of computing activity on these small handheld devices as well as solid-state drives (SSD).

- An emphasis on power efficient processor and device design, rather than purely high processing power; one of the beneficiaries of this was ARM, a British company which had focused since the 1980s on powerful but low cost simple microprocessors. ARM architecture rapidly gained dominance in the market for mobile and embedded devices.

With the call to Web 2.0, the period up to around 2004–2005 was retrospectively named and described by some as Web 1.0.[113]

Web 2.0

The term "Web 2.0" describes websites that emphasize user-generated content (including user-to-user interaction), usability, and interoperability. It first appeared in a January 1999 article called "Fragmented Future" written by Darcy DiNucci, a consultant on electronic information design, where she wrote:[114][115][116][117]

- "The Web we know now, which loads into a browser window in essentially static screenfuls, is only an embryo of the Web to come. The first glimmerings of Web 2.0 are beginning to appear, and we are just starting to see how that embryo might develop. The Web will be understood not as screenfuls of text and graphics but as a transport mechanism, the ether through which interactivity happens. It will [...] appear on your computer screen, [...] on your TV set [...] your car dashboard [...] your cell phone [...] hand-held game machines [...] maybe even your microwave oven."

The term resurfaced during 2002 – 2004,[118][119][120][121] and gained prominence in late 2004 following presentations by Tim O'Reilly and Dale Dougherty at the first Web 2.0 Conference. In their opening remarks, John Battelle and Tim O'Reilly outlined their definition of the "Web as Platform", where software applications are built upon the Web as opposed to upon the desktop. The unique aspect of this migration, they argued, is that "customers are building your business for you".[122] They argued that the activities of users generating content (in the form of ideas, text, videos, or pictures) could be "harnessed" to create value.

Web 2.0 does not refer to an update to any technical specification, but rather to cumulative changes in the way Web pages are made and used. Web 2.0 describes an approach, in which sites focus substantially upon allowing users to interact and collaborate with each other in a social media dialogue as creators of user-generated content in a virtual community, in contrast to Web sites where people are limited to the passive viewing of content. Examples of Web 2.0 include social networking sites, blogs, wikis, folksonomies, video sharing sites, hosted services, Web applications, and mashups.[123] Terry Flew, in his 3rd Edition of New Media described what he believed to characterize the differences between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0:

- "[The] move from personal websites to blogs and blog site aggregation, from publishing to participation, from web content as the outcome of large up-front investment to an ongoing and interactive process, and from content management systems to links based on tagging (folksonomy)".[124]

This era saw several household names gain prominence through their community-oriented operation – YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit and Wikipedia being some examples.

The mobile revolution

The process of change that generally coincided with "Web 2.0" was itself greatly accelerated and transformed only a short time later by the increasing growth in mobile devices. This mobile revolution meant that computers in the form of smartphones became something many people used, took with them everywhere, communicated with, used for photographs and videos they instantly shared or to shop or seek information "on the move" – and used socially, as opposed to items on a desk at home or just used for work.[citation needed]

Location-based services, services using location and other sensor information, and crowdsourcing (frequently but not always location based), became common, with posts tagged by location, or websites and services becoming location aware. Mobile-targeted websites (such as "m.website.com") became common, designed especially for the new devices used. Netbooks, ultrabooks, widespread 4G and Wi-Fi, and mobile chips capable or running at nearly the power of desktops from not many years before on far lower power usage, became enablers of this stage of Internet development, and the term "App" emerged (short for "Application program" or "Program") as did the "App store".

Networking in outer space

The first Internet link into low earth orbit was established on January 22, 2010 when astronaut T. J. Creamer posted the first unassisted update to his Twitter account from the International Space Station, marking the extension of the Internet into space.[125] (Astronauts at the ISS had used email and Twitter before, but these messages had been relayed to the ground through a NASA data link before being posted by a human proxy.) This personal Web access, which NASA calls the Crew Support LAN, uses the space station's high-speed Ku band microwave link. To surf the Web, astronauts can use a station laptop computer to control a desktop computer on Earth, and they can talk to their families and friends on Earth using Voice over IP equipment.[126]

Communication with spacecraft beyond earth orbit has traditionally been over point-to-point links through the Deep Space Network. Each such data link must be manually scheduled and configured. In the late 1990s NASA and Google began working on a new network protocol, Delay-tolerant networking (DTN) which automates this process, allows networking of spaceborne transmission nodes, and takes the fact into account that spacecraft can temporarily lose contact because they move behind the Moon or planets, or because space weather disrupts the connection. Under such conditions, DTN retransmits data packages instead of dropping them, as the standard TCP/IP Internet Protocol does. NASA conducted the first field test of what it calls the "deep space internet" in November 2008.[127] Testing of DTN-based communications between the International Space Station and Earth (now termed Disruption-Tolerant Networking) has been ongoing since March 2009, and is scheduled to continue until March 2014.[128]

This network technology is supposed to ultimately enable missions that involve multiple spacecraft where reliable inter-vessel communication might take precedence over vessel-to-earth downlinks. According to a February 2011 statement by Google's Vint Cerf, the so-called "Bundle protocols" have been uploaded to NASA's EPOXI mission spacecraft (which is in orbit around the Sun) and communication with Earth has been tested at a distance of approximately 80 light seconds.[129]

Internet governance

As a globally distributed network of voluntarily interconnected autonomous networks, the Internet operates without a central governing body. Each constituent network chooses the technologies and protocols it deploys from the technical standards that are developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).[130] However, successful interoperation of many networks requires certain parameters that must be common throughout the network. For managing such parameters, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) oversees the allocation and assignment of various technical identifiers.[131] In addition, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) provides oversight and coordination for the two principal name spaces in the Internet, the Internet Protocol address space and the Domain Name System.

NIC, InterNIC, IANA, and ICANN

The IANA function was originally performed by USC Information Sciences Institute (ISI), and it delegated portions of this responsibility with respect to numeric network and autonomous system identifiers to the Network Information Center (NIC) at Stanford Research Institute (SRI International) in Menlo Park, California. ISI's Jonathan Postel managed the IANA, served as RFC Editor and performed other key roles until his premature death in 1998.[132]

As the early ARPANET grew, hosts were referred to by names, and a HOSTS.TXT file would be distributed from SRI International to each host on the network. As the network grew, this became cumbersome. A technical solution came in the form of the Domain Name System, created by ISI's Paul Mockapetris in 1983.[133] The Defense Data Network—Network Information Center (DDN-NIC) at SRI handled all registration services, including the top-level domains (TLDs) of .mil, .gov, .edu, .org, .net, .com and .us, root nameserver administration and Internet number assignments under a United States Department of Defense contract.[131] In 1991, the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) awarded the administration and maintenance of DDN-NIC (managed by SRI up until this point) to Government Systems, Inc., who subcontracted it to the small private-sector Network Solutions, Inc.[134][135]

The increasing cultural diversity of the Internet also posed administrative challenges for centralized management of the IP addresses. In October 1992, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) published RFC 1366,[136] which described the "growth of the Internet and its increasing globalization" and set out the basis for an evolution of the IP registry process, based on a regionally distributed registry model. This document stressed the need for a single Internet number registry to exist in each geographical region of the world (which would be of "continental dimensions"). Registries would be "unbiased and widely recognized by network providers and subscribers" within their region. The RIPE Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC) was established as the first RIR in May 1992. The second RIR, the Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC), was established in Tokyo in 1993, as a pilot project of the Asia Pacific Networking Group.[137]

Since at this point in history most of the growth on the Internet was coming from non-military sources, it was decided that the Department of Defense would no longer fund registration services outside of the .mil TLD. In 1993 the U.S. National Science Foundation, after a competitive bidding process in 1992, created the InterNIC to manage the allocations of addresses and management of the address databases, and awarded the contract to three organizations. Registration Services would be provided by Network Solutions; Directory and Database Services would be provided by AT&T; and Information Services would be provided by General Atomics.[138]

Over time, after consultation with the IANA, the IETF, RIPE NCC, APNIC, and the Federal Networking Council (FNC), the decision was made to separate the management of domain names from the management of IP numbers.[137] Following the examples of RIPE NCC and APNIC, it was recommended that management of IP address space then administered by the InterNIC should be under the control of those that use it, specifically the ISPs, end-user organizations, corporate entities, universities, and individuals. As a result, the American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) was established as in December 1997, as an independent, not-for-profit corporation by direction of the National Science Foundation and became the third Regional Internet Registry.[139]

In 1998, both the IANA and remaining DNS-related InterNIC functions were reorganized under the control of ICANN, a California non-profit corporation contracted by the United States Department of Commerce to manage a number of Internet-related tasks. As these tasks involved technical coordination for two principal Internet name spaces (DNS names and IP addresses) created by the IETF, ICANN also signed a memorandum of understanding with the IAB to define the technical work to be carried out by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority.[140] The management of Internet address space remained with the regional Internet registries, which collectively were defined as a supporting organization within the ICANN structure.[141] ICANN provides central coordination for the DNS system, including policy coordination for the split registry / registrar system, with competition among registry service providers to serve each top-level-domain and multiple competing registrars offering DNS services to end-users.

Social Plugin